Raj Chetty’s study shows how friends impact low-income Americans

The Opportunity Atlas created by Raj Chetty and his team, answers the question: which neighborhoods in America offer children the best chances of climbing the income ladder?

August 13, 2022

If children of low-income parents grow up in counties in America where they can make friends with children from high-income families, “their incomes in adulthood would increase by 20% on average.” Overall, children from low-income families have far better prospects of attaining upward income mobility if they have friends from high-income families.

These are among the key findings of a study which analyzed data from 21 billion friendships on Facebook in the United States. Titled “Social Capital,” the study was published as two research papers in the journal Nature this month. It was led by Raj Chetty, a professor of economics at Harvard University, with co-authors Matthew O. Jackson, Theresa Kuchler and Johannes Stroebel, and input from 18 others, including four employees of Meta Platforms, the parent of Facebook.

The study also found that the number of friends a child from a high-income family has with those from similar income levels is far greater than the number of friends a child from a low-income family has with those from high-income families. About half of this gap “is explained by differences in exposure to people with high (income) in groups such as schools and religious organizations. The other half is explained by friending bias—the tendency for people with low (income) to befriend people with high (income) at lower rates” even when they meet regularly.

While Chetty’s conclusions from his latest friendship study, as well as those from his previous studies, are evident from anecdotal experience, his work provides data-based proof. As a result, his research, which analyzes major economic and related social issues in America, gets wide academic and media attention.

One of Chetty’s widely quoted studies, published in the journal Science in 2017, demonstrated the fading of the American Dream after World War II. It pointed out that about 90% of the children born in the early 1940’s went on to earn more than their parents. Since then, the economic advantages for the children have kept falling. Only about half of those born in the early 1980s went on to earn more than their parents.

Findings from other studies led by Chetty show the following: Elite colleges in the U.S. enroll more children from the top one percent of families, based on income, than from families in the bottom 60 percent; a black boy from a wealthy family is more than twice as likely to end up poor as a white boy from a wealthy family; and that teacher quality has a direct impact on students’ achievements.

Chetty has authored or co-authored 55 peer reviewed articles as well as written stories in the media. In 2012, Chetty was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, which came with a $500,000 grant. The next year, at age 33, he received the John Bates Clark medal, awarded to an economist under 40 whose work is judged to have made the most significant contribution to the field. Chetty’s “research has transformed the field of public economics,” the American Economic Association noted in a statement which announced his prize.

In 2003, he joined the University of California, Berkeley, as an Assistant Professor in Economics; he was named a professor in 2008. The next year, at age 29, he joined Harvard’s Economics Department, becoming one of the youngest tenured professors in the university’s history. He was also on the faculty of the university’s statistics department. In 2015, he joined Stanford University, where he also spent a year as a Professor of Sociology. Three years later he returned to Harvard as a Professor of Economics and is also on the sociology faculty.

Some of Chetty’s Harvard courses are available for free online. They include all 18 lectures of his introductory economics undergraduate course, Using Big Data to Solve Economic and Social Problems, which is available on YouTube. The introduction to the course has gotten nearly 30,000 views on the platform. The course, which was most recently taught at Harvard in Spring 2019, “had an enrollment of 375 students, one of the largest classes in the university.”

The topics covered in the course include equality of opportunity, education, health, the environment, and criminal justice. While it does not require any prior background in economics or statistics, the course introduces basic statistical methods and data analysis techniques, including regression analysis, causal inference, quasi-experimental methods, and machine learning. Chetty also provides free public access to a second year Ph.D. course.

Chetty earned a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard University in 2003, only three years after enrolling, which is a rare accomplishment. In 2000, he earned a B.A. in Economics also from Harvard, completing the four-year degree requirements in three years. In 1997, Chetty finished at the top of his high school class at the University School of Milwaukee.

Nadarajan (Raj) Chetty was born in New Delhi, India, and named after his maternal grandfather. In 1988, at age nine, he moved to the U.S. with his parents – his father Veerappa Chetty was a professor of economics and his mother Anbu was a professor of pediatrics. His parents are chettiars, a business caste in the state of Tamil Nadu who have traditionally been bankers and money lenders.

Chetty’s parents grew up in low-income families in the southern Indian state. Anbu learned English while attending a women’s college in a thatched roof structure in the town of Karaikudi, Chetty told The Atlantic. His two sisters are biomedical researchers and his wife Sundari, also a chettiar, is a stem-cell biologist.

Chetty is not content with merely analyzing socio-economic problems and especially wants others to have a similar opportunity to access college education like his mother was lucky to have in India. In 2018, he returned to Harvard to teach as well as set up and run the non-partisan, not-for-profit Opportunity Insights, which “seeks to translate insights from rigorous, scientific research to policy change by harnessing the power of ‘big data’ using an interdisciplinary approach.”

The major funders of the organization are the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, run by Microsoft founder Bill Gates and his former wife Melinda Gates, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, set up by Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, and his wife.

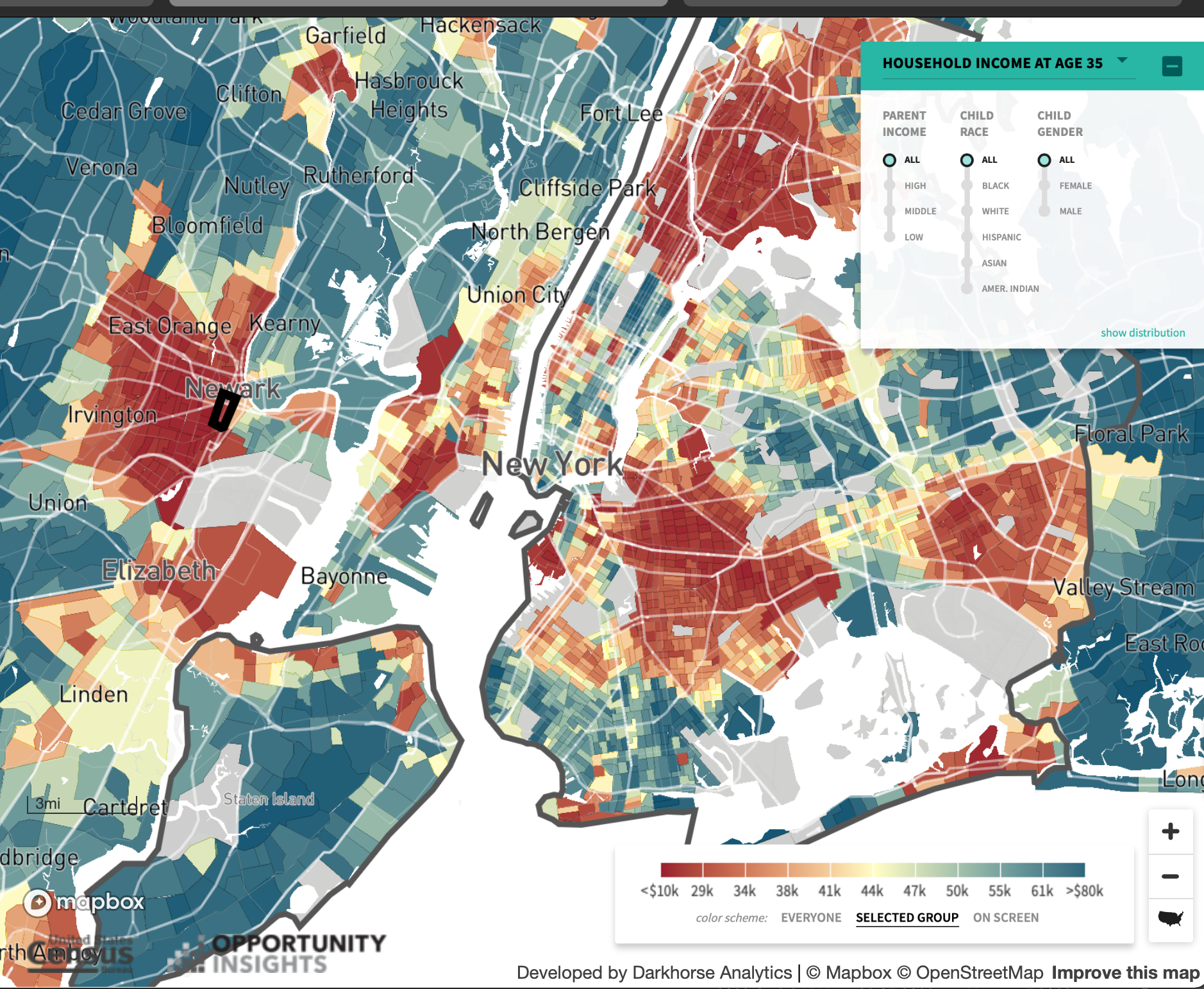

In 2018, Chetty’s non-profit released the Opportunity Atlas, a free interactive mapping tool to answer the question: which neighborhoods in America offer children the best chances of climbing the income ladder? The atlas traces the roots of outcomes such as poverty and incarceration back to the neighborhoods in which children grew up. The atlas enables policy-makers and others in a community to see exactly where and for whom opportunity is lacking. It was built using anonymized census data on 20 million Americans who were in their mid-thirties.

The Opportunity Atlas map for the New York City area. The blue areas are those where children have the best chances of attaining higher incomes in adulthood while children in the red areas have lower chances.

Opportunity Insights is partnering with colleges and universities which together enroll one million students for four-year degrees and another 2.4 million at the two-year community college level, representing more than 15% of the entire U.S. undergraduate students. The goal is to “understand not only which colleges act as engines of intergenerational mobility, but why, and how schools and policymakers can promote opportunity and economic growth by helping large numbers of low-income students reach the middle-class.”

Starting in 2018, Chetty’s team partnered with the Seattle and King County Public Housing Authorities to test a new program which provided housing search assistance, connections to landlords, and financial support to low-income households. An evaluation found that the “services dramatically increased the share of families who moved to high-opportunity areas.”

Opportunity Insights is seeking to partner with other U.S. counties to replicate the program. Yet no new initiatives are listed on its website. Is this because of the major obstacles faced in legislating and funding such policies?

Typically, in middle and upper class neighborhoods, there is strong opposition to permitting housing for low-income tenants. Current social welfare schemes to tackle education, jobs and housing have been place in the U.S. for decades. So there are millions of Americans making a living off such schemes, from government and non-profit employees to consultants, researchers and some school and college teachers. Politically influential, they lobby aggressively against any new programs that may hurt their income and jobs. Then there are the long-entrenched political divisions on funding programs for the poor.

In addition, children of all races, growing up in low-income homes and neighborhoods, face several major obstacles to get a better education and find high-income jobs: many teenagers have to supplement family income by taking on entry-level jobs and neglect their education; predominance of economically or otherwise unstable, single parent households; and socio-economic compromises that make families appear to have little focus on the value of education, when this may or may not be the case.

Even so, Chetty is an optimist who believes that economics is now a science - due to big data analytics using machine learning and other new technology tools - which can help improve income mobility. He sees the Opportunity Atlas as being analogous to the microscope whose discovery around 1,600 led to the development of modern medicine.

In 2021, some former students at Harvard built a similar atlas for India, though it provides only broad insights due to the inadequate size and quality of the data. According to the data, Chetty noted in a virtual talk while accepting the 2020 Infosys prize, the proportion of sons in Indian Muslim families, who earn more than their fathers, is low and has kept falling: from about 32% for sons born in the mid-1960’s to around 27% for those born in the 1980s. The income mobility for Muslims, he adds, is the lowest among all caste and religious groups in India.

The study on Social Capital in the U.S., published this month by Chetty’s team, is part of the solution to the puzzle he intends to solve to find out which factors nurture income opportunity and those which block it. If upward mobility can be measured with enough precision, then it can be understood; if it can be understood, then the process can be altered to enable more people to achieve upward mobility, he told The Atlantic. While his initial goal is to find anything that helps, “The big-picture goal is to revive the American dream.”